Animated Cities #1: London

A tour of animated representations of the Big Smoke, from 'Peter Pan' to 'Steamboy.'

Welcome to Animated Cities, a new mini-series of posts. In each instalment, I’ll look at animated films and series set in a major city—or rather, in the artists’ idea of that city, which, as we’ll see, can vary hugely from one work to the next. I’ll kick things off with my hometown, London. Get out your tube maps…

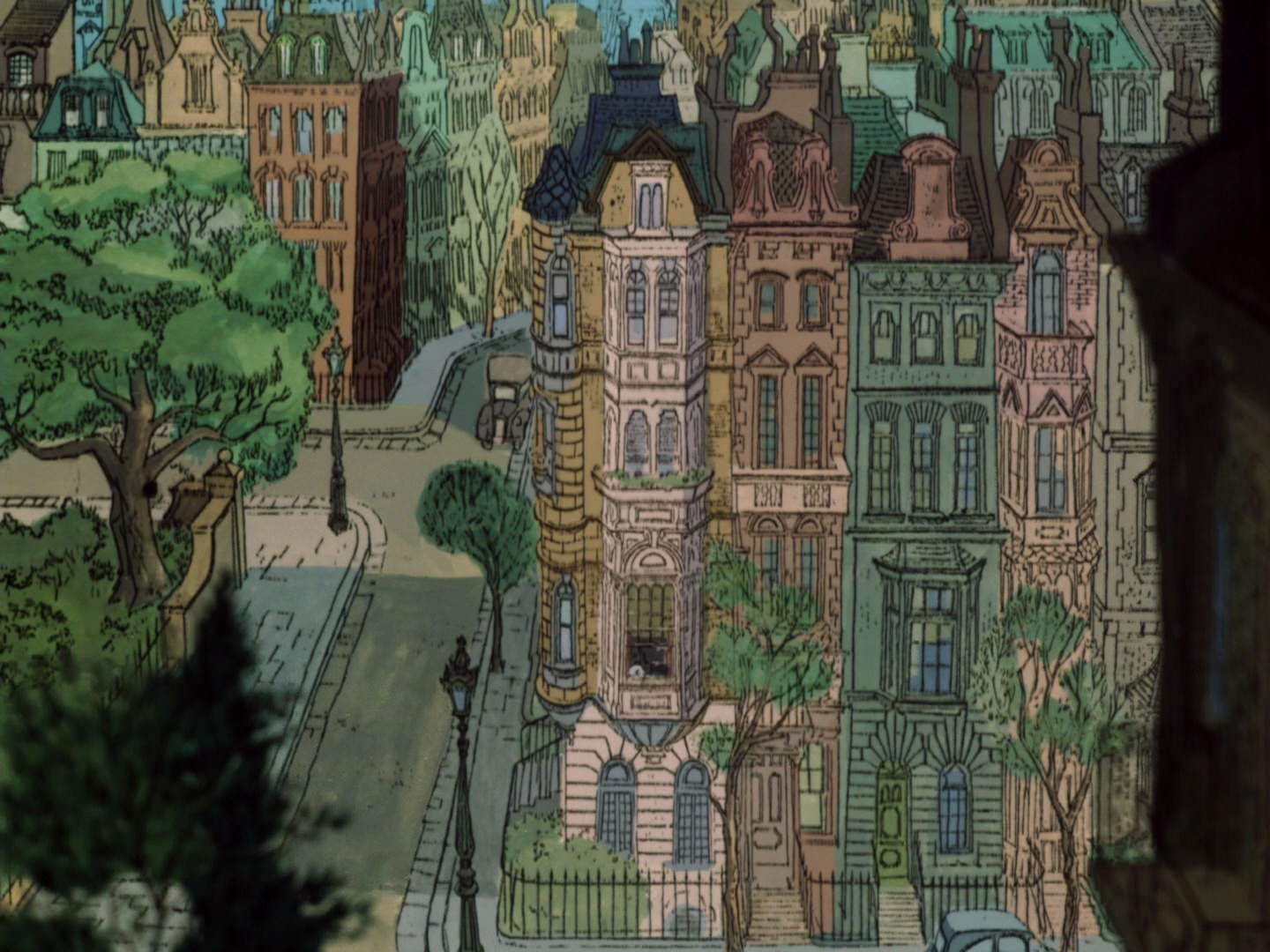

Is it any wonder that Roger, the striving songwriter in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), has such a sunny demeanour? After all, he leads a charmed life on the edge of London’s prim Regent’s Park, in one of the city’s most desirable neighbourhoods. We can only question his decision to sell up and move to the countryside at the end (especially in light of today’s property prices in the area).1

To be exact, Roger lives somewhere even more desirable than Regent’s Park: namely, the film’s version of Regent’s Park, which is more appealing than the real place. London in Dalmatians is a quaintly time-worn city, its scuffed old-world charm conveyed through the muted colours and crumbly linework of the backgrounds.2 This sketchy style, as easygoing as Roger himself, casts a casual romance over every location—including Primrose Hill, the starting point for the famous Twilight Bark sequence, which is a spot I associate more in real life with muggings than evening dog walks.

The film’s art direction is largely the work of the great Ken Anderson, who deployed a new photocopying method to transfer drawings directly from paper to cel, bypassing the team who normally did this manually. As a result, the characters retained something of the animators’ loose linework (which human inkers would have tended to clean up); the technique was applied to the backgrounds too, and coupled with flat use of colour. Old-world charm aside, this approach to design was quite modern, breaking with the textured, painterly backgrounds of previous Disney films.

For a more traditionally Disneyish vision of the British capital, we need only wind back eight years to Peter Pan (1953). We see less of London here: it is essentially a portal between the Darling children’s bedroom and Neverland. But there is time for a few exterior shots of the family’s Bloomsbury home upon a slightly hazy lamplit night—an archetypal London atmosphere. We’re treated to a few establishing aerial shots of the city, then a whistlestop tour of its landmarks as the kids fly past them on their way to Neverland. In an elegant double-dissolve near the end, the moon in Neverland becomes Big Ben’s face, then that of the grandfather clock in the Darling home: the journey home elided into a few seconds.

Big Ben pops up left and right in London-set animation, often plonked into the background as a cosy icon of the city. It is a symbol ripe for subversion. Enter another Disney film, The Great Mouse Detective (1986), which riffs on the Sherlock Holmes stories. A late-Victorian gloom hangs over the world; there is much scurrying down (yes) foggy lamplit alleys and waterfronts, and because the characters are mice, several exterior backgrounds are closeups of bricks or paving stones. This is a very brown film, and ever so slightly dull. But it does conclude with an inspired action sequence set both on and inside the great clock tower (inspired, that is, by Hayao Miyazaki’s The Castle of Cagliostro [1979]). The chase upward through Big Ben’s turning gears is a brilliant and terrifying bit of staging in depth, and an early example of CGI use in a Disney feature. (Disney would return to the clock’s interior at the end of Pixar’s Cars 2 [2011], which uses the space far less imaginatively.)

Probably more than any other character, Sherlock forms a bridge between London and animation. There have been countless adaptations of Conan Doyle’s stories. I could mention Sherlock Gnomes (2018), whose climax is set among the internal mechanics of another landmark: Tower Bridge. Miyazaki himself had a go, directing some of the series Sherlock Hound (1984–85), which recasts the characters as dogs. With its colourful facades and clear skies, the London here is a far cry from the murky city in The Great Mouse Detective, providing a suitably picturesque backdrop to the show’s gently magical steampunk shenanigans.

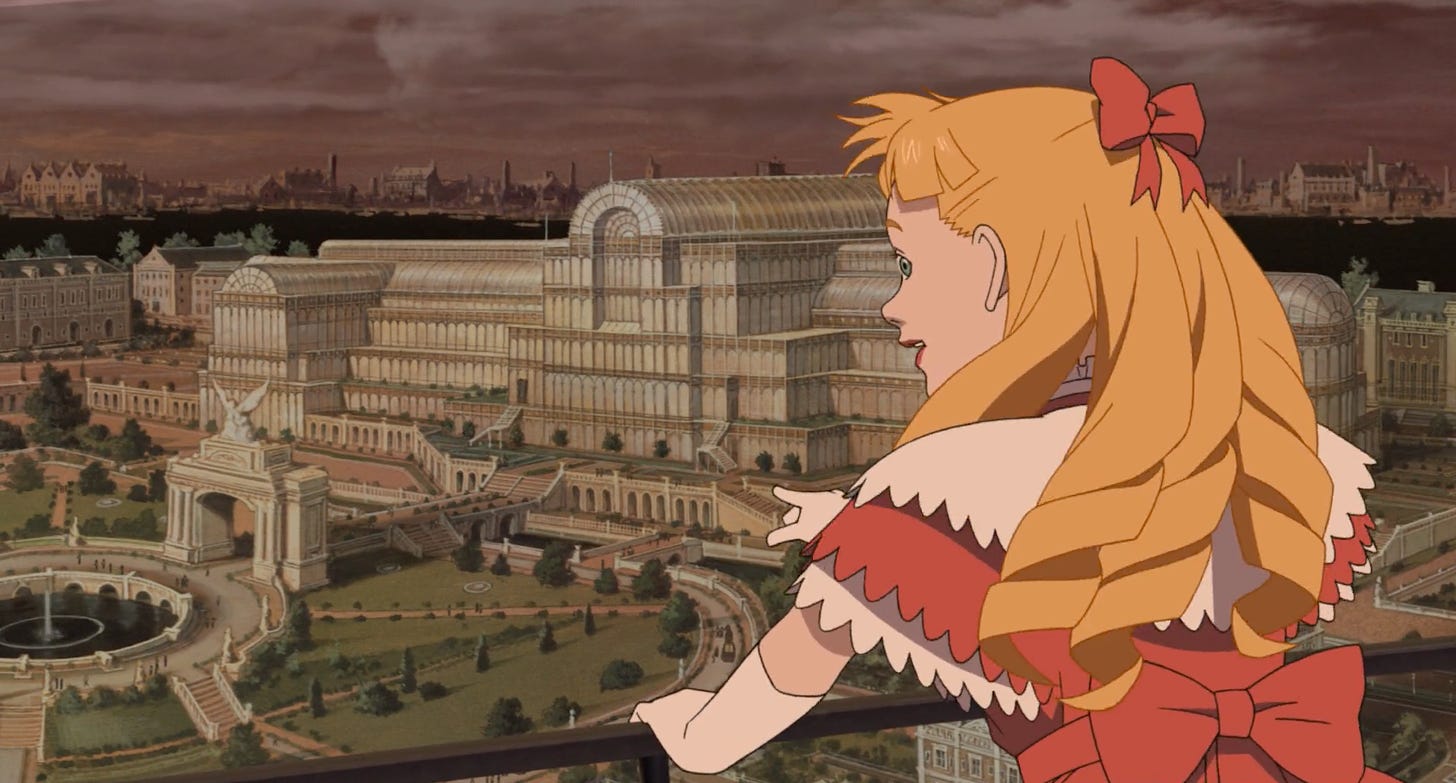

Of course, Victorian London is a spiritual home of steampunk, and no animated film tackles either the setting or the genre as rigorously as Katsuhiro Otomo’s Steamboy (2004), which is set around the Great Exhibition of the mid-19th century. Those who have seen Akira (1988) will know the precision with which Otomo creates his worlds (in Steamboy, with art director Shinji Kimura). The London of Steamboy is exquisitely, almost oppressively detailed. Its centrepiece, a version of the mighty Crystal Palace (transposed here to a riverside location), is showcased from all angles, including the interior; you can count the panes of glass if you want to. The backgrounds are impressive, but there is something cold about their meticulousness, as befits this austere morality tale of scientific progress.

The same era is depicted in Richard Williams’s adaptation of Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1971), minus the steampunkery and plus smog. This film is gloomier even than any of those mentioned above. Like Steamboy, it is rich in period detail, and the two films show us a similar view of the Holborn Viaduct and St Paul’s. But the clean lines of Steamboy are nowhere to be found here. Chuck Jones, who produced, had set Williams and his London-based crew the challenge of recreating the steel-engraving illustrative style popular in the mid-19th century. The result is an exercise in dense sketchy texture and desaturated palettes; the city is like another ghost in the story. It is a wonder that the team pulled off this tricky style in the nine months they had. To meet the deadline, Williams recalls doing nine backgrounds a day himself, as well as animating and directing.

Among Williams’s crew was Roy Naisbitt, an artist with a supreme talent for technical designs. He would become Williams’s chief layout man, conceiving the diabolical architectural confections for the unfinished feature The Thief and the Cobbler. Neil Boyle, another Williams acolyte, later brought Naisbitt out of retirement to create a sequence for his short film The Last Belle (2011), which ranks as one of the most thrilling minutes of London-set animation ever created. Late for a blind date, the alcoholic protagonist rushes into an underground station (unnamed but near St Paul’s), only to fall down the stairs then careen wildly through its tunnels and platforms. Naisbitt deploys his mastery of warped perspective, shuttling us through this tiled labyrinth until we no longer know which way is up. The sequence isn’t just a marvel of draughtsmanship but also an unnervingly accurate representation of what it’s like to be drunk—or, for that matter, what’s it like to try to find your way around one of the capital’s bigger tube stations, even when sober.3

By and large, the works mentioned above take place in London kind of by default; the characters don’t talk about the city much. But in Naoko Yamada’s K-On! The Movie (2011), a spin-off from the anime series about high-school girls who form a band, London is not just a setting: it’s a destination. Partly drawn by its rock history, the girls spend a holiday there, sightseeing and gigging by day and hanging out in the Earl’s Court Ibis hotel by night.

The characters’ giddy excitement powers the narrative: they are fascinated by taxi doors and dog-poo bins in parks, and thrilled at the chance to play at a festival on the South Bank. The movie features plenty of famous spots, but also incorporates areas and details beyond the usual chestnuts. The girls’ poor grasp of English leads them astray, so that they end up in unspectacular places like Aldgate East. This may be the only animated film to feature a Ryman’s stationery shop and an O’Neill’s pub. And yet, for all the mundane details, this may also be the animated film that takes the most pleasure in being in the capital.

The stylised portraits of cities we find in animation often retain the landmarks, and can play with them beautifully, as in the Big Ben sequence in The Great Mouse Detective or the showdown on an 11th-century London Bridge in Vinland Saga (2019–). But when the action moves elsewhere, an anonymity tends to creep in. If a live-action film is shot in a suburb, that suburb is represented in the film; locals will recognise it. Background artists on an animation production may use reference images from a specific area, but the particularities of that area can end up obscured by their creative interpretation, so that the setting effectively becomes an unspecified part of London.

Unless it is named, of course. Danger Mouse (1981–92), the classic Cosgrove Hall children’s series starring the titular rodent spy, revels in London in-jokes, including frequent references to dramatic events in the very nondescript suburb of Willesden Green. Danger Mouse’s HQ is inside a Royal Mail postbox on Baker Street (Sherlock again), and many episodes are set in London. The series’s longevity means that it covers a lot of ground: the characters visit all kinds of (specified) areas, which are mostly rendered in the show’s clean 2D style but sometimes in a clashing quasi-photographic aesthetic. But the city is also regularly cast as a character—indeed, as a victim of dastardly plots, awaiting rescue while buried under snow or covered in a giant spider web. The capital is not just a place to live in but to protect and cherish.

Perhaps the most locally specific animated film of all is a borderline case. Jonathan Hodgson’s Feeling My Way (1997) is only animated in part. The short film is built around footage the director shot on his walk to work, from Islington to Soho. Hodgson annotates these live-action images, drawing over them to indicate the thoughts prompted in him by the things he sees; sometimes the entire frame breaks into (essentially rotoscoped) animation which abstracts elements from his environment, revealing what stands out to him.

Simply and artfully, Feeling My Way depicts the dynamic tension between the outside world and our interior processes through which our impression of a place is born. All the Londons in animation are, really, cities of the mind, filtered and expressed through the imagination. Hodgson’s film hints at how this process begins.

A note before I wrap up. I was sad to learn last week of the death of Emma Calder. She was a wonderfully idiosyncratic filmmaker and a warm, fun presence at screenings and festivals. She also played a key role in the lobbying of the British Film Institute to launch a dedicated fund for short-form animation, which it eventually did in 2019. Those who don’t know her works could do worse than start with The Queen’s Monastery (1998), which is spare and dynamic and elegant.

Yes, I know he has to house his pooches somewhere. I admire his devotion to them.

The art direction in One Hundred and one Dalmatians, along with the rest of the production, is discussed Charles Solomon’s chapter on the film in The Walt Disney Film Archives. The Animated Movies 1921–1968 (edited by Daniel Kothenschulte).

Boyle wrote about his collaboration with Naisbitt on his blog. It’s worth a read.

This is a wonderfully insightful article! I particularly liked the way you described London as “a spiritual home of steampunk” in your discussion of Steamboy. The depth of your analysis, combined with the variety of animated works, paints a vivid picture of the city. It's an engaging and well-rounded read that leaves you eager for more.