Forever Changes: Horror, Animation And 'The Wolf House'

Animation is good at scaring us. It should do so more often.

I’d like to return to this question of genres, which kind of haunts animation discourse. A few posts ago, I quoted the mantra popularised by Guillermo del Toro: “Animation is a medium, not a genre.” This is really a statement about animation’s potential. The trouble is that, in reality, animation is still too often reduced, by those who make it and watch it, to the handful of genres for which it is deemed appropriate.

Typically, that means variations on comedy and fantasy, made with young viewers in mind. Animation is a wonderful partner for these genres, both of which have been closely associated with it since its earliest days. Musicals are central to the story too, with Disney at the spearhead.

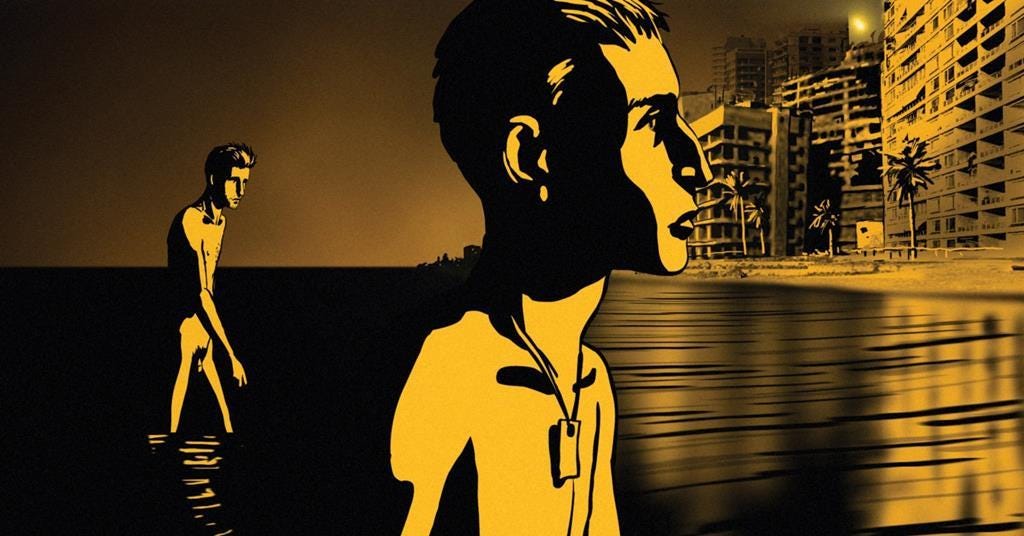

There have also been smaller examples of pigeonholing along the way. For decades, American networks have been obsessed with animated sitcoms. And in recent years, independent producers in Europe have shown a penchant for animated dramas about war and migration—a trend which is surely connected not just to current affairs but also to the twin triumphs of Waltz With Bashir (2008) and Persepolis (2007).

Amid all this, there is one area that animation has remained notably uneasy with (one might even say scared of): horror. I’m not singling it out because it is the rarest of genres. Someone looking for animated horror will come across plenty of examples (especially in Japan, or among shorts); they might be harder-pressed to find animated westerns. But I do think it is the most underused, given how suited animation is to generating fear and unease. This won’t change as long as the idea prevails that animation is basically for kids.

Which is ironic, because ostensibly family-friendly animated films are rife with frights; many people were administered their first screen scare via animation. I don’t mean what TV Tropes might call “defanged horror”: works that borrow the trappings of the genre without intending to really frighten (like, say, the Hotel Transylvania movies). I’m talking about the vengeful dwarfs chasing the witch to the cliff-edge in Snow White (1937) or the parents’ eyes turning to buttons in Coraline (2009). Moments, cloaked in otherwise reassuring stories,1 that viciously exploit the insecurities already present in us in childhood.

In one sense, animation is good with horror for the same reason that it is suited to fantasy (and sci-fi): it can easily depict things and places that don’t exist, including the eeriest or most gruesome creations. Phil Tippett’s Mad God (2021) is a journey through a circle of hell unknown even to Dante, teeming with vicious monsters that look like nothing from reality. And if the much-delayed live-action remake of Akira (1988) ever gets made, I wonder how they’ll tackle the giant scarred teddy bear in the hallucination sequence. Will they just resort to animation? Will they cut the scene?

Animation can also do unsettling things with time. This is a more rarefied approach to horror, exemplified by the short film Revolver (1994; watch below). We are shown a sequence of surrealist vignettes which may represent the last thoughts of a drowning man. Each scene is looped, forming a hermetically sealed cycle—an effect that would be difficult to create naturally in live action. We feel trapped in a claustrophobic eternity.

Perhaps most powerfully of all, animation can disturb us by deploying one of its defining tools: transformation. Now, transformations can be benign: when the Beast morphs butterfly-like (back) into a human at the end of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (1991), we are meant to be relieved. They can be funny: when the huge baby in Spirited Away (2001) is magicked into a little mouse, his danger is neutered, sublimated into comedy. But they can also be dead scary: that giant teddy in Akira is assembled from dozens of innocent objects lying around the room. In fact, turning a character or object into something scary is only one strategy. A skilful filmmaker can also use the mere threat of metamorphosis to disconcert us, to undermine our sense of what is real. Done well, this can be terrifying.

Exhibit A: The Wolf House (2018), a stop-motion feature by the Chilean duo Cristóbal León and Joaquín Cociña which has become something of a cult classic (watch the trailer below).2 The premise is harrowing in itself. Young Maria flees a remote colony to dodge punishment for some vague transgression and takes shelter in an abandoned house, whose only other residents are two strange pigs. Clues link the story to the real-life Colonia Dignidad, a commune founded in Chile by an ex-Nazi which was involved in torture, sexual abuse of children and other atrocities (and which had ties to Pinochet).

Despite some clear symbolism (at one point, a window morphs into a swastika), overt historical commentary is not the film’s approach. It is more interesting in showing the world—and the inner world—of a child completely destabilised by life in the colony, telling its story as a kind of warped fairy tale.3 The house is supposed to be Maria’s refuge: there is a literal wolf at the door who, though never seen, can be heard trying to tempt her back to the colony. But we can’t shake the feeling that the beast is already, somehow, inside.

Barring a frame narrative involving a documentary about the colony, the film is confined to the house, incorporating paint-on-wall and object animation, as well as giant puppets—sculptures, really. There are certainly horrific images in The Wolf House: jets of black liquid issuing from the eyes and mouth of an infantile figure, for one. But more than that, it is the complete volatility of the place that unsettles us.

The sculptures are forever shape-shifting, falling apart and reassembling; a threatening object banished from the space can always reappear. Painted figures slip across the walls, apparently confined to the flat surface, until they sprout a limb that reaches into the room. Perspectives flip: a wall becomes a floor. Time flows wrongly: clock hands dance insanely about. Character designs are abruptly altered and apparently inanimate objects start moving of their own accord. The greatest transformation affects the pigs, which gradually turn into Aryan children who may not mean well. The camera never stops moving. There are no cuts.

This condition of ceaseless change is established right away, so that we learn to trust no appearances. From the start, we are robbed of our faith in the consistency of things, which is a precondition for feeling safe. Maria finds herself not in a refuge but in a nightmare. There is something here about the impossibility of privacy within a cult or indeed a dictatorship (a giant surveilling eye sometimes appears on the wall). Even more frightening is the sense that Maria’s very system of reality may have been disordered during her time in the colony, leaving her struggling to distinguish the truth in things and unable, however hard she tries, to resist the wolf’s dark spell.

The volatility is anchored in León and Cociña’s unusual approach to the production, which was largely improvised and moved from location to location.4 But it is latent in all animation, where nothing need be stable in space or time. The effect can be magical, and it can be diabolical.5

I’ve left it till late in the post to acknowledge that the concept of genre is a slippery one. Some may quibble that none of the films mentioned above are “true” horror (but then any other label they might apply instead would be equally open to challenge). Definitions rest on sets of conventions that are always shifting and being debated; it’s the evolution of these conventions, in fact, that keeps a genre alive. When it comes to films that frighten us and teach us things about ourselves in the process, animation is armed with powerful tools of its own. If these can broaden our understanding of what horror is, the genre will be all the better for it.

Coraline may be a bad example: I’m not sure whether it really ever is a reassuring film.

Among the fans of León and Cociña’s horror is Ari Aster, who invited the duo to collaborate with him on the animated sequence in the middle of Beau Is Afraid (2023). He is executive-producing their next animated feature, Hansel and Gretel.

The framing of Chile’s far-right past through dark fantasy and the occult is a favourite approach of León and Cociña’s. They do something similar in their stop-motion short The Bones (2021) and the mostly live-action feature The Hyperboreans (2024), which premiered at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes last month. But those films strike different tones from The Wolf House. The Bones is a pastiche of silent-era animation, while The Hyperboreans come across as a kind of guignolesque metafictional comedy, albeit one with frightening moments of its own.

The ever-reliable Animation Obsessive has an excellent process piece on the film.

The notion of the inherent changeability of all things can also be political, and I think this is a part of León and Cociña’s vision, too.

First and foremost. I wanted to state that this is a very artistic film. I love the imagery. It reminds me of things I seened before in films like the Conjuring and It. However, I wished I felt the weight and dread of the situation. I guess what I'm trying to say is that I wished it had been a feature length narrative. Instead of a short that felt like an acid trip. You are so right in your analysis. Animation hasn't really pushed the envelope with the horror genre. It tip toes around it. It's as if people think horror is just about grossing you out with gore or scaring children.

Yes indeed. There is not enough info on this topic. Thanks for posting this. Yes. Japan anime and animated shorts from around the globe have featured legit nightmarish imagery but, I dream of the day when one of us creates a horror animated film that is on Par with the Exorcist, Hereditary and other frightful cinematic classics. Walt Disney asked himself this question when he and his team were in the midst of making Snow White. Can an animated film make you cry? He learned that yes. It could. What we as filmmakers need to ask ourselves now is this. Can an animated film make the hairs stand on the back of people's necks? Can animation make audience members faint or run out of the theatre in legit terror, the way the Exorcist did in the winter of 73'? I don't know. However, those of us who love Horror as a genre and animation as a medium should do everything in our power to find out. That should be our life's mission. I know that it's mine.