Foxes, Lego, Clay Heads: Animation And The Canon

Here are 10 films that deserve the BFI Film Classics treatment.

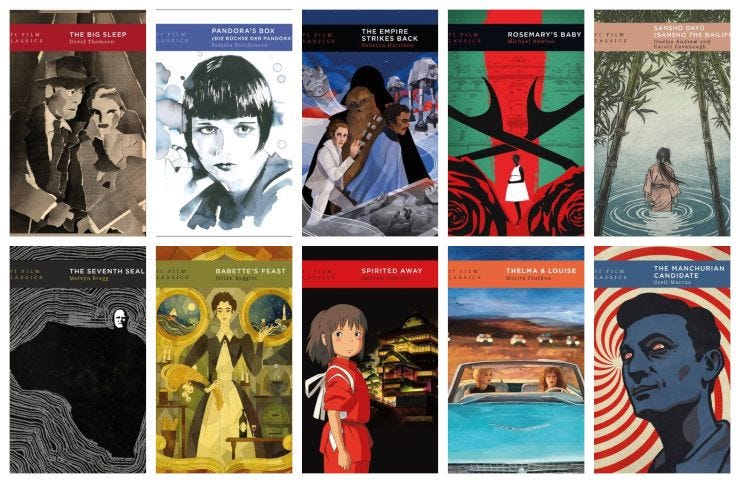

One of the British Film Institute’s many gifts to cinephiles is its Film Classics,1 a series of 100-odd-page books each of which weighs up the place of a great film in history. They are idiosyncratic texts, taking different approaches depending on the film in question and the interests of the author (who is often but not always an academic). They have taught me much about films, and about criticism.

As often with canon-making in cinema, animation is sidelined,2 accounting for only five of the 200-plus Film Classics in existence: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Toy Story, Akira, Spirited Away and Grave of the Fireflies, the last of which I wrote.3 There are as many on the films of Powell and Pressburger alone.

My desire to see more animation in the series was one of the reasons why I pitched a book on Fireflies. I was also drawn to the way in which this beautiful film upends common preconceptions about animation, telling a story of unsparing bleakness. The editors accepted and encouraged me to find my own angles on the subject; I appreciated their openness.

As I was writing the book, the publishers signalled in a press release about the series that they were ready to broaden the canon. I hope that this means more animation, and indeed more animation outside usual suspects Disney, Pixar and Studio Ghibli.

In that spirit, I’m suggesting 10 animated films that I think deserve a Film Classic.

I’ve left out films that already have a book dedicated to them in English, which means no Tale of Tales, no Yellow Submarine, no Waltz With Bashir, no Who Framed Roger Rabbit (still the gold standard for animation-live action hybrids). But I have included shorts, as they are so central to animation history; the Film Classics series has covered at least one live-action short (Meshes of the Afternoon), so I think that gives me licence.

Other than that, I’ve tried to hew to the Film Classics’ declared remit to “introduce, interpret and celebrate landmarks of world cinema and television.” The films have to be important, whether because of what they do with the medium, the context of their production or the influence they have had. I’m not just picking my favourites (that list would look different).

Within these rules, my choices are obviously subjective, and I’m aware there are absences that will make a different film fan mad. There is nothing from mighty studios like UPA, the Fleischers and Toei; nor from great directors such as Yuri Norstein, Tex Avery, Satoshi Kon, Ralph Bakshi, and Wendy Tilby and Amanda Forbis. I could have expanded the list to 20, 30 or even 50, and the beautiful thing is that it would still have been woefully incomplete.

If you have suggestions of your own, I’d love to hear them in the comments section below.

The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Lotte Reiniger, Germany, 1926)

As the oldest extant animated feature, Prince Achmed is important by default, a triumph of endurance—the film’s cut-out animation was painstakingly produced over three years—and technical innovation (the team employed a kind of proto-multiplane camera). More than that, Reiniger’s adaptation of tales from One Thousand and One Nights is extraordinarily atmospheric, her lead-and-cardboard marionettes beauties of filigree precision. The film has projected its influence across the ensuing century, influencing sequences in Steven Universe and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1. Bonus: the BFI has the oldest print and released the Blu-ray in the UK, so it should be amenable to the idea of a Film Classic.

The Tale of the Fox (Ladislas Starevich/Irene Starevich, France, 1937)

Like Reiniger, the Russian-born Ladislas Starevich was a pioneer. Through vision and necessity—these were the early wild-west days of animation—he invented his own rules. He was fond of animating dead insects, but in this feature, made (with his daughter, a frequent collaborator) after his exile to France, he uses conventional puppets to recount the medieval tales of Reynard the Fox. Ninety years on, France’s first animated feature still charms with its parade of tap-dancing mice, drunk hares and gladiatorial wolves. Echoes of the film reverberate throughout Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox.

Begone Dull Care (Norman McLaren/Evelyn Lambart, Canada, 1949)

This is the trickiest sell in the list: an eight-minute experimental film whose narrative, such as it exists, is steered by the lines and rhythms of the jazz soundtrack. It’s a joyous and masterful example of abstract animation, a vast tradition that is written about too little. The film also provides a way into discussing the remarkable body of animated work from its producer the National Film Board of Canada, with which McLaren was so closely involved. Begone Dull Care is animation as visual music, universal language. No wonder it continues to inspire artists around the world. Discussing this film, the animator Kim Keukeleire once told me, “I am more interested in moving emotions than moving objects.” That captures the film’s effect perfectly.

Duck Amuck (Chuck Jones, US, 1953)

Because we need a Jones film, a Warner Bros. classic, a nugget from the so-called Golden Age of Animation. Why Duck Amuck out of the dozens of options? Because, in the most playful way, this famous film is about nothing less than animation and filmmaking: red meat for critics. Daffy Duck enters his greatest conflict yet, against his maker—that is, his animator, whose pencil and brush intervene in the frame (and who turns out to be Bugs Bunny). Through Daffy’s increasingly existential mishaps, Jones draws our attention to the facets and materials of animation production: colouring, framing, background art; linework, paint, the film reel itself. In the funnest way, it speaks about the labour of animation, a useful corrective to the Walt Disney-ish notion that these films are almost magicked into being.

The Snow Queen (Lev Atamanov, Russia, 1957)

A film about an ice-cold sorceress is also a story of the Cold War. A team of artists at Soyuzmultfilm, Russia’s great state animation studio, set out to make a feature-length Hans Christian Andersen adaptation that could rival Disney; the result has not only remained a classic in its home country, it was also—improbably—released in the West at the time, becoming a Christmas staple on American TV. It was also well received in Japan, inspiring a young Hayao Miyazaki to stay working in animation at a time of doubt, and traces of its tale are found in his works Shuna’s Journey and Princess Mononoke. Along with Yuri Norstein’s shorts, The Snow Queen must rank as the most influential animated film from one of the great animation nations.

Where Is Mama? (Te Wei, China, 1960)

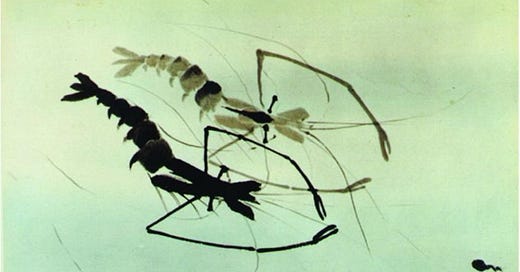

Few films look like Where Is Mama?, which somehow succeeds in animating a watercolour style inspired by the beloved Chinese painter Qi Baishi—a technical feat that yields a gorgeous result. The simple story of tadpoles looking for their mother contains a propagandistic message about the importance of state protection. No wonder: the backdrop is Mao’s China, and as with Begone Dull Care and The Snow Queen, the film is a window onto a formidable state apparatus, in this case the legendary Shanghai Animation Film Studio. Te may be the least known director in this list, but he probably had the most extraordinary life, ending up imprisoned by the authorities, only to stage a remarkable comeback after the Cultural Revolution. Where Is Mama? offers a way to talk about the fascinating period of Chinese animation history spanned by his career.

Dimensions of Dialogue (Jan Švankmajer, Czechoslovakia, 1983)

Švankmajer is the great surrealist of European animation, his (mostly) stop-motion works teeming with flamboyant metamorphoses, familiar objects in strange contexts and scenes that seem plumbed from the deepest tier of the subconscious. Working behind the Iron Curtain in defiance of the suspicious authorities, he built up a global cult following that includes Guillermo del Toro and Terry Gilliam. This short is his best-known, and perhaps best, work: a delirious triptych about communication in which food is shredded and clay bodies merge, but not a word is spoken.

Creature Comforts (Nick Park, UK, 1989)

I wanted to include an animated documentary, as it is such a popular form nowadays, but I’ve settled on a film that only half-meets the definition. Park, who also created Wallace & Gromit, here interviews ordinary folk about their homes; using the recordings, he reimagines them as plasticine zoo animals discussing their incarceration. Like Duck Amuck, the short stands as a very witty commentary on its own medium, in this case revealing how visual accompaniment can alter the meaning of words. One of a string of thoughtful shorts with documentary soundtracks produced by Aardman, it spawned a series of its own, as well as an ad campaign that was influential in its use of vox pops.

Mind Game (Masaaki Yuasa, Japan, 2004)

I like to think of this film as anime’s equivalent of The Velvet Underground’s first album: the ultimate cult gem, a cauldron of ideas, its influence out of all proportion with its reach (Satoshi Kon was among its many admirers). Starting off as apparent gangster fare, the narrative swerves into a freewheeling metaphysical journey of self-discovery, complete with a Pinocchio-style trip into the belly of a whale. Yuasa directs with such freedom, really pushing the animation, perspective, designs—and shifting between visual styles when it suits him. He’s since become one of the few festival-approved “auteurs” of anime, and the studio he founded, Science Saru, one of the most interesting in the country.

The Lego Movie (Phil Lord/Christopher Miller, US, 2014)

Does any animated film better capture the tone of pop culture in the past decade? The deep irony, the scattergun references, the curious spectacle of a big-studio production peddling an anti-corporate message (up to a point, of course): The Lego Movie showed how to do a sassy IP adaptation in the late-capitalist age. It launched a franchise and a mini-boom in toy movies, leading up to Gerwig’s Barbie and Pharrell’s own Lego film; it turbocharged sales of the plastic bricks; and it confirmed Lord and Miller as perhaps the most interesting filmmakers in Hollywood animation. This wouldn’t have happened if it wasn’t very enjoyable, sharply written with a slick mock-stop-motion CG animation style.

They aren’t literally gifts: we’re talking RRP £12.99, which is reasonable, considering the exorbitant prices that books from academic imprints can reach. The BFI’s current publishing partner on the series is Bloomsbury.

There have been a fair few attempts at creating a canon for animation alone, including the Jerry Beck-edited The 50 Greatest Cartoons, Andrew Osmond’s 100 Animated Feature Films, and Skwigly’s feature “100 Greatest Animated Shorts”. There’s room for more. But it’s the scant attention given to animation within wider film canons that I find most frustrating.

A Film Classic on Kiki’s Delivery Service is in the works.

Great stuff! The inclusion of Prince Achmed feels so obvious in retrospect that it's kind of shocking the BFI hasn't done it already -- it *needs* to be covered. There's also a strong case to be made for one of Trnka's films, probably The Hand, given its international fame compared to some of his other stuff (although The Emperor's Nightingale would be another contender).

This is a pretty good list! I recently watched Mind Game for the first time, and it was a trip. For other recommendations, how about Richard Linklater's Waking Life? Or maybe a film by Marcell Jankovics?

Also, I think you make a compelling case for The Lego Movie. However, if we're going to have a Lord/Miller production in the Film Classics series, I would argue that, depending on how part three comes out, (or even if part 3 doesn't turn out so well) do a book on the Spider-verse trilogy.

In terms of influence, Into The Spider-verse has impacted the trajectory of mainstream CG animation significantly. The success of Spider-verse paved the way for stylized CG animation in many recent efforts, including-- Puss in Boots 2, TMNT Mutant Mayhem, Nimona, and arguably to disastrous and misguided results in Disney's Wish.

The films are also interesting as they how they exist in the current super hero ecosystem. On the surface, they share some characteristics of other contemporary super hero films, they are filled with tons of fan service and obscure lore. However, these are films that people who have zero interest in MCU movies enjoy. (like myself, I haven't watched a Marvel movie in years, and never bothered to go to the cinema to see one) So that tension of existing inside the super hero umbrella, while setting itself apart from it may be worth discussing. Super heroes are a part of the contemporary film landscape, so the Film Classics series might as well discuss one of the good ones!

I'm excited to read your blog Alex, good luck as it continues to grow!!