'Images Heard And A Music Seen': A Conversation With The Brothers Quay

The twins discuss their film 'The Doll's Breath' in this interview from the archives.

On Thursday, the Brothers Quay will premiere their third feature at the Giornate degli Autori in Venice. Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass is their long-awaited adaptation of the novel of the same name by Bruno Schulz, the Polish author whose writing inspired their short Street of Crocodiles (1986) and has influenced their work more broadly. Like their previous features, Sanatorium mixes live action with stop motion.

I’ve always been mesmerised by the Quays’ troubling, unearthly films, and I’ll gladly take this excuse to pull an article out from the archives. Around the premiere of their last film, the short The Doll’s Breath (2019), I interviewed the pair for the French animation review Blink Blank (read the article, in French, in its first issue from January 2020, available in print and digital editions here). With the magazine’s kind permission, I’m printing below the original English-language transcript, which has never been published before.

In their relentless quest to rationalise and classify, critics have pinned all kinds of labels onto the Brothers Quay’s enigmatic oeuvre. Most often, they resort to some variant of “Mitteleuropa of the mind”—a reference to the pantheon of Central European filmmakers, writers, composers and graphic designers who have been the most conspicuous influence on the twins’ works of puppet animation (and, at times, live action).

But this description doesn’t quite fit. For one thing, some elements of the Quays’ films that are held up as evidence of their European sensibility—trams, the shadow of industrial decline—are also features of Norristown, Pennsylvania, where they grew up before emigrating to England in the 1970s. For another, it belies their omnivorous cultural appetite and openness to chance encounters, which are sustained by regular travel across the world.

For their new film, the 22-minute The Doll’s Breath, the Quays actually turn to a Uruguayan writer, Felisberto Hernández—or rather return, as they have worked with his writing before. Like most of the twins’ films, this one acknowledges a literary source—Hernández’s novella Las Hortensias, a portrait of a fiendish love triangle between a married couple and a life-sized doll—without adapting it in any conventional sense. Rather, the Quays reimagine those episodes from Hernández’s text that best capture the emotions and ambiances they have gleaned from the story. The scenes unfold in a sequence that’s concerned with the progression of these moods above all. The whole is tied together by the Quays’ signature cinematic language: fast edits, looped shots, intense close-ups, quivering objects, unstable light.

Alongside Hernández’s, one other name precedes the Quays’ in the end credits. Michèle Bokanowski is a French composer of chiefly electroacoustic music; the Quays have long been familiar with her scores for the films of her husband, Patrick Bokanowski. Her 2002 work L’Etoile Absinthe, a propulsive, synthesiser-led piece, provides the soundtrack to The Doll’s Breath. Its dissonant jabs and sub-auditory rumbles speak jealousy and paranoia in the absence of any dialogue.

Before starting production, the Quays always find their score first. If literature sometimes sets off their imagination, music, which they call their “secret scenario,” guides it. Music sets an example, authorising them to develop their films through intuition and feeling, more than narrative rigour. That intuitive process is laid bare in their startling visual analogies, the idiosyncratic rhythm of their editing; the Quays trust us to follow, if not necessarily understand. This is what makes their films feel so intimately theirs—a quality to which talk of Mitteleuropean influence fails to do justice. It is what alienates some viewers and commands such loyalty from their fans, including one Christopher Nolan, who personally commissioned The Doll’s Breath.

The Quays compare Bokanowski’s score to a “vast planet,” strange and overwhelming. In that spirit, I’d like to evoke another label that’s sometimes applied to their work. They make “UFO cinema”1: films of ambiguous provenance and striking technical sophistication, which restlessly explore their own private planets.

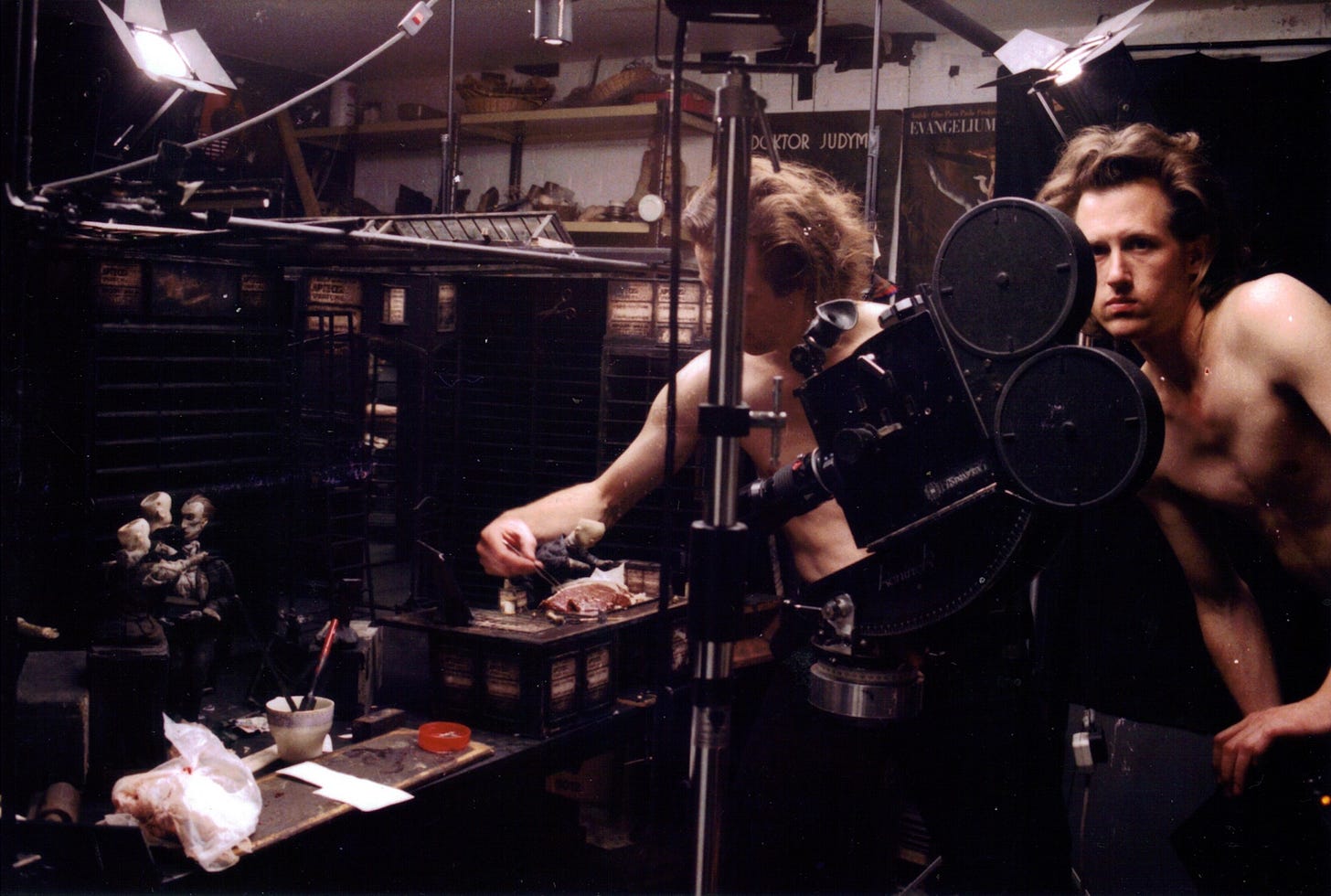

In earthlier terms: the Quays are based in South London. They handle almost all aspects of their animated films’ production, from set building to editing. For thirty years, they have worked inside a cluttered studio whose half-drawn curtains guard its obscurity. I met them there to talk about The Doll’s Breath and their artistic approach in general.

ADdW: How did Christopher Nolan become involved?

Quays: In 2015, Christopher very graciously restored and curated a selection of our 35mm short films. This programme, which subsequently travelled about the States, was entitled The Quay Brothers in 35mm. The films were The Comb (1990), In Absentia (2000) and Street of Crocodiles; the programme included his short documentary film on us, called simply Quay (2015).

We can only conjecture how Christopher may have been drawn to our world. Perhaps it is the infinitely great stopped short by the infinitely small. His is the vast macrocosm set against our thoroughly more modest microcosm.

The Doll's Breath was then commissioned by Christopher and his wife [and production partner] Emma Thomas in 2016. Their only stipulations were that it had to be no longer than 30 minutes, and shot in 35mm. We had two beautiful 35mm Mitchell cameras that had been used as deluxe doorstops in our studio for the last 15 years, so we only had to resuscitate one of them.

Was the shift back to film a happy one?

Yes, in principle, it was a renewed pleasure to be shooting again on 35mm. But it was a little bit of a shock to receive the rushes not as a 35mm work print, but as depressingly ungraded digital files that had to be downloaded the following day at noon. So the only time we ever physically touched and handled the film was to load and unload the camera each day. After that, the so-called vocabulary of film per se vanished.

With respect to the film, Christopher left the choice of subject matter to us entirely. We chose as inspiration Felisberto Hernández’s novella Las Hortensias in which Horacio, a former window dresser dreading a future without his wife, creates a replica of her. In rear rooms his assistants arrange elaborate tableaux behind glass vitrines with life-sized dolls. Complicated charades ensue where his wife, her simulacra and the dolls change places in a web of jealousy, betrayal and murder. To these deliria, we added Max Ernst’s Loplop character as Horacio’s shadowy alter ego.

When did you discover Hernández’s writings?

When we premiered Street of Crocodiles in Paris [watch a clip below], we’d been reading a book in which Julio Cortázar talked about a Uruguayan writer, Felisberto Hernández, and how remarkable his fictions were. That very day we walked past a bookshop and there in the front window was displayed a volume of “Felisberto Hernández,” freshly translated into French. The title was Les Hortenses. Thirty years later, we’ve made a film inspired by that very same story, which premiered in Paris [at L’Étrange Festival], no less.

In the English translation, Hernández’s story is titled The Daisy Dolls. Why did you change the title to The Doll’s Breath?

It is our way of making a personal homage to Felisberto and, above all, of attempting to transpose the literary text to the independent realm of sound and image. That has always been our first impulse—the same with Bruno Schulz or Robert Walser [whose writings have inspired many films by the Quays].

The sheer weight of Felisberto’s text alone would shatter the wood of our puppets. A “daisy doll” was a cheap 1970s commercial doll manufactured in Hong Kong. For us, it in no way corresponded to Felisberto’s epoch nor to the rendering of the actual title, Las Hortensias. This was the name of the family in the story, but also means the plant “hydrangea,” which is Greek for “water vessel.” [One of the dolls in the story is filled with water in order to be made more life-like.] Our reference for the life-sized dolls in the story was Giorgio de Chirico.

As for the title The Doll’s Breath, this was our reading of the conclusion of the story: Maria, Horacio’s wife, perpetrates a revenge by sentencing him to a supreme madness whilst “breathing” violently a new life for herself.

You are familiar with a breadth of films and literature dealing with puppets. What is striking about Hernández’s vision in the story?

Felisberto knew indisputably well the shadowy recesses of objects and things unnamed. Cortázar might have been speaking of Felisberto when he stated that he was searching for “another order, more secret and less communicable; that the true study of reality did not rest on laws, but the exception to those laws.” A Felisberto Hernández in the provincial backwaters of Uruguay could have said this with equal incisiveness and forlornness.

His prose has a synaesthetic quality. So, I think, does your work: it often foregrounds music, scent, and the delicate haptic aspect of the puppets as they interact with the sets and each other. Is this a useful way to view your films?

In an ideal world, yes. We find it impossible not to feel compelled to explore this potential force-field of climates within a scenographic space: the synthesis of colour (by which we also mean black and white in all its myriad gradations), the quality of light, the choice of lenses, depth of field, sound and music, along with the collective sum of textures, all contribute to these sensations and disturbances. They are intoxicating minefields that can manifest themselves in the service of a film’s richness and subjectivity.

How did you go about adapting the story? Did you write a script?

Christopher did ask for a script, so we wrote a very detailed one. We followed the course of the story pretty strictly, but—as always when we work—at some point you have to just put the script down, and as you start to build the puppets, it takes its own course. You just guide it a little bit: shorten some things, get rid of some things.

There’s always that thing in the back of your head: you’re creating a script for, say, the British Film Institute. So you’re trying to be lucid, make a coherent thing that they’re going to look confidently at, and say, “Thanks, here’s the money, see you in two years.” With a certain honesty, we try to write that script, but know fully that once you start constructing the space, you can’t hold to that. It’s not like a live-action shoot where you schedule shots. We have the so-called privilege of disregarding that, or going in another direction.

Can you recall the circumstances in which you first heard Michèle Bokanowski's music L'Etoile Absinthe?

We’ve known Michèle and Patrick Bokanowski since 1986, and their remarkable collaborations together. Recently, at the Alchemy Film Festival on the Scottish Borders that we attended with Michèle and Patrick, she slid us a CD. It contained two pieces: Chant d’Ombre and L’Etoile Absinthe. Both were fabulous, and we just looked at one another and smiled. Then slowly, upon repeated listening, we realised that L’Etoile Absinthe proved to be the bleakest and most emotionally devastating.

Although we submitted a script and treatment to Christopher, for us, the music has always been the secret scenario in which to elaborate the film’s real journey through space and time. Our films have always obeyed musical laws rather than dramaturgical laws. Ultimately the deep symbiosis you search for is that of images “heard” and a music “seen.”

The score combines synths and the human voice. This seems appropriate to a story that is, in large part, about the tension between—and merging of—the mechanical and the organic. Was this on your minds when you picked this music for this film?

There is in this piece of music a truly mesmerising seduction, with its endless overlapping waves of toxic sound, punctuated by the trembling of eerie silences on the very threshold of hearing, which subsequently become more and more demonic. Truly this was a music of the spheres, and one that could perhaps be harnessed to the final madness of Horacio imprisoned in one of his own glass vitrines.

What Michèle does is to work with analogue tapes and loops… We’re speaking very generally here, but for us, [this process] has to be a little mysterious. For us, Michele’s music is about the “sound” that you hear, which shouldn’t be analysed into components [such as which instruments are playing]. She talks about “cinéma pour l'oreille” [“cinema for the ear”]—clearly something she conceived while making the music for Patrick’s films. This corresponds with what we’ve always imagined—images heard and a music seen—before ever being aware of Michele’s own take on it.

[Her music is like] a vast planet, [by which we mean] the rawness of the music to the ear in all its vastness and in its particular musical language. In the same way, Karlheinz Stockhausen [who wrote the music for the Quays’ In Absentia] achieves a sound realm by not using standard instruments, which becomes even more “cosmic” as such. This, above all, is also a very specific deployment of subjectivity on our parts. With Karlheinz and Michèle, we have this massive wall of sound that we see as a vast sound painting.

Elements of The Doll's Breath, such as the unravelling string at the end, put me in mind of “bachelor machines”—a term you have used to describe a range of contraptions in your films. Its definition varies widely. What does it mean to you?

The unravelling of the string merely mirrors Horacio’s own mental disintegration, so for us it’s not really a “bachelor machine.” However, the standard definition is that they are useless, incomprehensible machines, sometimes delirious. Yet when we employ them, they become inevitably meaningful: they can be enigmatic worlds functioning in complete isolation, and yet, clearly, they can mirror the inner workings of any narrative.

Given the organic manner in which your films develop, when do you know that a film is finished?

Not one of our films has ever ended as we had anticipated. What had been written in the scenario as a thoroughly plausible ending inevitably finds another ending, which gets discovered en route. The music invariably becomes the final arbiter.

Critics have called your work both “deeply intellectual” and “deeply intuitive.” Can these two qualities be reconciled?

There seems to be a prevailing opinion that being intuitive with one’s visual sensibility cannot also be rigorously intelligent.

You’ve said that you seek to “free the text from its literary side.” Why “free”—what is constraining in literature?

Cinema is for us foremost about images, and in that respect the word simply must loosen its authority.

Below: the Brothers Quay’s music video for “Are We Still Married” by His Name Is Alive.

Your last two films, Maska (2010) and Unmistaken Hands: Ex Voto F.H. (2013), used voiceover, which is quite unusual in your oeuvre. Why not this time?

In The Doll's Breath, we felt it imperative to tell the story purely with images and music, even if it became abstract. With Unmistaken Hands, the quality of the Hernández text in Spanish was poetic, subjective and reflective. In Maska, Stanisław Lem’s text in Polish was withering, and propels the narrative with a scalpel’s precision. In both these instances, the very sound of the voiceovers literally becomes a second layer of music.

Although he’s from the other side of the world, Hernández has a lot in common with the other writers who have most inspired you: Kafka, Schulz, Walser. The grotesque sensibility, the dark-brown angst.

We always say that they could have all crossed on one street corner in Vienna at the same moment, caught by some anonymous photographer unbeknownst to all of them. Of course, it was that potential. And of course it never happened—but we know that Kafka read the feuilletons of Walser and loved them. Whether Felisberto read Kafka or Schulz or Walser is less known, but Schulz had read Kafka’s The Trial.

You are at work on an adaptation of Schulz’s Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. How much can you say about that?

We have almost a half hour of footage that has been filmed already. It’s meant to be 75% animation and 25% live action. There are entire animation sequences that we’ve already completed with sound and music and a voiceover.

In the script for the film there’s a live-action auctioneer; he is auctioning off an ornate wooden box resembling a funerary cabinet, called “Maquette for the Sepulchre of a Deceased Retina.” It contains the late retina of the owner of the box, who has randomly placed seven magnifying lenses with tiny adjustable screws; many are very old, so there is a little touch of distortion in them which we like very much. Each lens holds a glimpse of one of the seven final images that the said eye beheld. And when the funerary box is positioned correctly, the sun’s rays are organised to strike once yearly, on the 19th day of November—the day on which Schulz died—“liquefying” the dead retina and thereby anointing each of the seven images and setting them into motion. So that’s the premise for the film; we’ve only done a small portion of the animation.

A direct translation of the French term film ovni, used to describe works that resist classification.

too cool

I LOVE ITT, I’m young and have never heard of these artists, today I’m going to the Theather to see Coraline again, I love stopmotion so much