Richard Williams, Imogen Sutton And An Enthralling New Memoir

Sutton speaks about the book she wrote with Williams, her late husband and longtime collaborator.

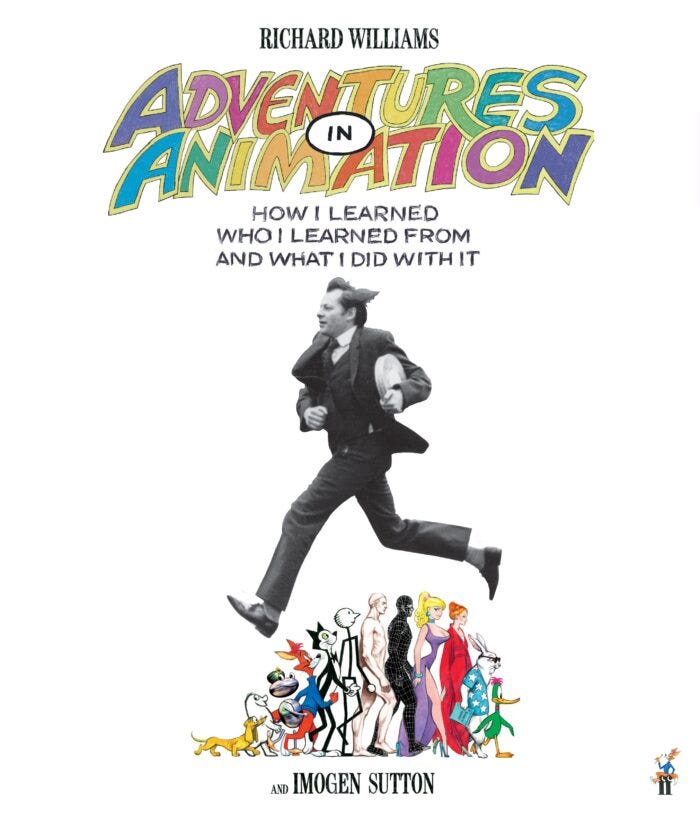

Each year, I head to Annecy Festival with a novel in my bag and the fanciful notion that I’ll find time between screenings to read it by the lake in the sun. This year marked a breakthrough: I did manage to read my book, gorging on its sweeping narrative so that I actually finished it before the week was up. This time, it wasn’t a novel but a memoir, and a fitting one for Annecy: Adventures in Animation: How I Learned Who I Learned From and What I Did With It, by Richard Williams and Imogen Sutton.

Five years after his death, Williams continues to fascinate the animation world. A virtuosic artist and quixotic filmmaker, he could seemingly animate anything, and led projects of intimidating ambition. It is he who oversaw the animation in Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), still the gold standard for combining animation and live action, and who directed A Christmas Carol (1971) in the style of steel-engraving illustrations from Dickens’s time—a fiendishly difficult task achieved at breakneck speed. He went on to codify all he’d learnt about traditional animation in his book The Animator’s Survival Kit (2001), which remains perhaps the go-to manual for students and pros the world over. Yet for all his brilliance as a teacher, his career also contains cautionary tales, not least around the tortuous production of his unfinished magnum opus The Thief and the Cobbler.

So Adventures in Animation is a posthumous release, and a bit of a patchwork too. Alongside his other qualifications, Williams was a raconteur, and here his life story is told from start to finish in breezy, anecdotal style. We’re treated to vivid stories about colleagues and relatives, manic productions and frightening road trips. There are digressions in which he pays tribute to the Golden Age animators who inspired him, such as Emery Hawkins and Milt Kahl. The book groans under the weight of its images: archive photos, storyboards, concept artwork, the beautiful drawings of Williams’s illustrator mother and more. Then, as we reach the later stages of his life, the format changes: because Williams died before he could complete the book, Imogen Sutton steps in to finish the story in her own voice.

Her voice is crucial to the story, after all. Sutton was Williams’s wife and collaborator for 35 years, playing a critical role in his projects over that time. For example: as his producer, she had the presence of mind to make and keep a copy of The Thief and the Cobbler as it was on the day Williams lost control of the film to his studio, Warner Bros.; thus she preserved a director-approved (but still unfinished) version that has since been titled A Moment in Time. She recounts this whole episode in riveting detail in Adventures in Animation, as well as her subsequent work with Williams on his now-famous lectures (which gave rise to the book The Animator’s Survival Kit) and later projects. Sutton is also an established filmmaker in her own right, having directed documentaries on Simone de Beauvoir and animator Art Babbitt, among others. It was in fact while visiting his studio for a documentary that she met Williams.

In other words, Adventures in Animation is very much in keeping with the couple’s previous projects: it is a true collaboration. Though structured unconventionally, it is clear and readable throughout, and full of valuable details for anyone interested in not just Williams or animation production but the creative life in general.

To learn more about how the book was conceived and put together, I put some questions to Sutton, who kindly answered by email. Williams was known to her and others as “Dick” (just as she is often “Mo”), so that’s how I refer to him below.

ADdW: Adventures in Animation was born out of ideas that were initially for The Animator’s Survival Kit. How was it decided that these should be spun out into a separate book?

IS: There were chapters Dick initially wrote for The Animator’s Survival Kit on the great Golden Age animators he knew and worked with. However, it was clear that they weren’t right for that book, which concentrated on the principles of animation. Those chapters were put aside, but were not the “core” idea for the new book, which was to be a memoir and account of a life in animation. But they did become a central part of it.

You write that you and Dick agreed this book would be a joint venture. Can you say more about how you collaborated on it?

We collaborated on everything we did for 35 years. We had different skills and talents—but on any project we did, we worked very closely together. There was the initial idea that there might be a memoir, but that got put aside to work on film projects like Prologue [a short film completed in 2015; watch it below].

The book emerged organically over time. Dick regularly had a hot chocolate in the Aardman canteen [he was based at Aardman’s studio in Bristol, England in his later years], and the younger animators gathered round and enjoyed his stories about the animators he had known and the life he had led. We started to think about what such a memoir would look like: how would it incorporate Dick’s work, our work together and the relationships he’d had with the great animators. The structure of the book was carefully thought out, weaving all those aspects of Dick’s life.

How did you go about accumulating all the materials you and Dick used to create this book? In particular, what materials were you drawing on when completing the book without him?

There was no shortage of materials. Dick had already started writing lots of notes and even completed some handwritten finished pages which are at the front of the book.

I’d made a number of films about Dick and his work, as well as films about other animators, whose interviews appear in the book. There were many events we did over the years which were filmed, as well as recorded conversations Dick had done with some of the animators. Also, I’d made a film about Art Babbitt. So there was plenty of material to draw from. Plus a plethora of drawings, photographs, storyboards, stills and family memorabilia.

Adventures in Animation covers Dick’s entire life. I found it really quite moving. What was it like for you both to work on something so intimate? Were there things about his life that you didn't know until this project?

I’m touched by your comment that you found it really quite moving. We worked so closely together that to work on this book was an extension of all of that. We were both interested in the process of making such a book and of course its content. It was such a natural thing for us to do after working together for 35 years that it all just flowed. There wasn’t anything particular that I didn’t know about Dick’s life, but the nuance he gave certain things was emotional for me.

Watch Williams speak about legendary Disney animator Milt Kahl below:

In general, what did the writing process mean for Dick—did it come easily to him? Did it give him creative fulfilment?

Dick was multi-talented and one of his many talents was writing. He would never have claimed that as a talent, but I insisted on letting him know what a good and natural writer he was. Once he got going with the writing, he gave it his full concentration, as with everything he did. He was happy we’d made the decision to go ahead with the book and really enjoyed the process as it went along.

You say Dick was always learning. What was he learning from in his later years?

All his life, Dick never stopped being curious, allowing himself to be influenced and learn from other great artists. He went to exhibitions, saw films—both contemporary and historic—and listened to music. A favourite event each year was to go to the Giornate del Cinema Muto [a silent-film festival] in Italy, which is mentioned in the book. We saw some incredible silent films which stimulated both of us creatively. Ideas would flow after we’d been to the Giornate.

Did teaching and writing about animation over the years change the way Dick approached his art?

I don’t think it changed the way he approached his art. But the teaching and writing was helpful to his work. He often joked that he too had to refer to his own book sometimes.

You write about The Thief and the Cobbler: A Moment in Time, which you were pivotal in bringing about. I was at the BFI screening of it in 2018, and Dick was visibly emotional when introducing the film. I got the sense he still found it difficult to talk about it. Other than the amazement you describe feeling when you first viewed the print in 2000, what emotions did the process of revisiting and reconstructing the film bring for you and Dick?

The business of losing the film and then “reconstructing” it about 20 years later was intense. Our reaction to the way the film was lost was to get off the battlefield and go back to basics. This meant that when we had the chance to digitise it and save it as it was on the day we had it taken away, we could do it without any bitterness or grief—just the sheer joy and amazement that we had this second chance. As Dick said in his introduction to the screening you saw, “This film does not have a sad ending.”

Is there any chance we’ll get to see those completed minutes of A Call to Arms,1 his unfinished final short, one day? I notice that the film has a title now, whereas before, if I'm not mistaken, you weren’t naming it...

I very much want to make it possible to be able to screen A Call to Arms. Dick loved working on it and I was constantly amazed by what he was animating.

Adventures in Animation: How I Learned Who I Learned From and What I Did with It is published by Faber & Faber and is out now.

In related news: recordings of Williams’s lectures, which are also known as The Animator’s Survival Kit, have until now been available only as a 16-disc DVD boxset—but they are coming to streaming. Bloomsbury will start rolling the collection out to academic institutions in January 2025, and subscriptions for individuals will become available in the summer.

A Call to Arms was to be the next chapter in the film project begun with 2015’s Prologue. The project was to be a retelling of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, which Williams had been fascinated with since his teenage years. Sutton writes: “He planned to animate the film alone, using only pencil and paper. The film was to be one continuous shot – he would draw the camera moves. This was to be the culmination of a lifetime of work and study.” It was Sutton’s idea to break the project down into short films to make it more manageable. A Call to Arms “would introduce the main women characters and their plan to go on a sex strike to stop the war … [T]here was to be a mix of serious political activism and comic, bawdy dialogue.”