In the family VHS collection I grew up with, nestled among the Disneys and Rosie and Jims, was a tape that terrified me, gave me a surprise psychedelic experience and cemented my childhood love for Rupert the Bear, all in one.

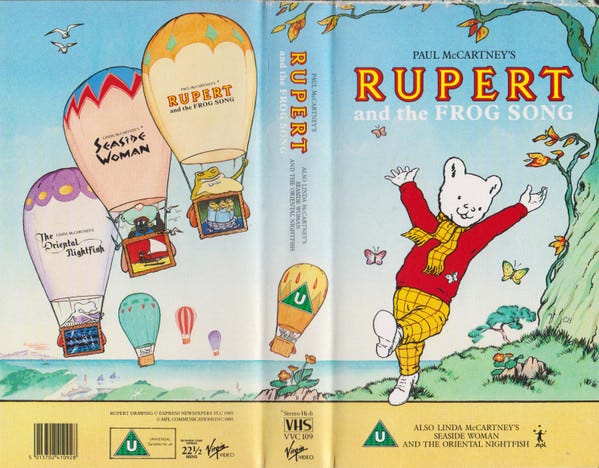

I’ll start by describing the video’s cover art, to give you a sense of what unsuspecting parents might expect they were buying. Rupert stands near the sea in his trademark red jumper and yellow checked scarf and trousers, reclining with arms outstretched, as if tickled by the same breeze that’s shaking the autumn leaves around him. The sea stretches across the spine to the back cover, where colourful hot-air balloons dot the blue sky, their canvas adorned with the names of the three animated films on the video, along with thumbnail images too small to reveal much. The mood is tranquil. The certificate is U.

The VHS does open with a Rupert film,1 albeit one which has little to do with the scene on the cover: the short Rupert and the Frog Song (1984). Then follows Seaside Woman (1980), a Caribbean-set short that’s devoid of bears but does at least feature a sea view. The tape then lurches into its final act: The Oriental Nightfish (1978), a four-minute gothic acid freak-out in which a naked woman is blasted by a jet of cosmic energy and spends the ensuing minutes tripping through various geometric environments.

It’s this last film that makes the collection so bizarre, so subversive. It feels like the tape has been spiked. But there is a thread running through the collection: all the films feature songs by Paul or Linda McCartney. I didn’t understand this as a child. I don’t think I even knew who Paul and Linda were. I certainly didn’t recognise Paul in the live-action intro to the Rupert film, which is set in an apparent recreation of the singer’s childhood attic. I just kind of accepted (as children are wont to do) that these films came together, and let The Oriental Nightfish bury itself into my subconscious, where it would sit uneasily for decades to follow.

Returning to these films as an adult, I understood the link at last. And I was surprised to learn something else: critically and commercially, the shorts were a triumph. The VHS was the UK’s best-selling video of 1985 in the UK, according to Paul’s official site. The films earned a Grammy nomination, a Palme d’Or and a BAFTA. In fact, they represent the cream of British animation talent of the time.

Let’s start where the video does: with Rupert. Paul had a bit of an obsession with him. Like me, he would read the annuals as a child. One of his first moves after the breakup of the Beatles was to acquire the film rights to the character. He developed an idea for an animated feature, dreaming of Disney-style production values and penning a bunch of songs. Bootlegs can be found online, but one was officially released: “We All Stand Together,” which Paul recorded with former Beatles producer George Martin.2 This is the titular “frog song” that features in the animated short on the video, which was intended as a pilot for the feature.

For those who don’t share my and Paul’s fondness for Rupert, a quick recap. Created as a comic strip for the conservative British newspaper the Daily Express in 1920, the anthropomorphic bear embarks on adventures to magical places, often with his animal pals, while also exploring the countryside, not unlike Enid Blyton’s Famous Five. He lives in an eternal interwar rural idyll, in which nature is lush and varied, and any sense of threat is annulled by the safety of his family home, to which he invariably returns at the end. The Rupert stories typify a very English nostalgia that struck a chord with Paul, who was always prone to backward-looking sentimentality.

Rupert and the Frog Song fits the template. Rupert (voiced by Paul himself) sets out for a walk, catches up with his buddies Bill Badger and Edward Elephant, gambols in the hills, then comes across a mysterious cave, inside which he witnesses a rare event: a performance by a secretive choir of frogs. Cue the song, a delightfully bouncy novelty track that’s up there with “Yellow Submarine.”3 The performance unfolds, complete with orchestra, operatic carp, and a frog king and queen on a lily pad. As it wraps up, a sinister owl swoops down, sending the frogs back into hiding. Rupert heads home and excitedly tells his mother what he saw. (The video below is an abridged version; the whole film is available on YouTube.)

It isn’t much of a story—the film’s function as a pilot is showing through—but in the manner of the best Rupert tales, it is wonderfully surreal and slightly ominous. The director is Geoff Dunbar, an essentially self-taught animator who came up through London’s busy commercials industry before making two striking independent shorts: the Palme d’Or-winning Lautrec (1974), inspired by sketches by the great painter, and Ubu (1978), an adaptation of Alfred Jarry’s raw absurdist play. The latter caught Paul’s eye. With its coarse humour and aggressive, sketchy style, it’s a far cry from the slick prettiness Frog Song, but the ex-Beatle was convinced.

Dunbar was eventually hired as director, later saying that his ability to retain the ideas of the original Rupert artists, Mary Toutel and Alfred Bestall, is what convinced Paul. He oversaw a talented team: among the animators is Eric Goldberg, who would go on to animate the Genie in Disney’s Aladdin and co-direct Pocahontas. While the animation isn’t quite top-tier Disney, it is full, rounded and characterful, bearing the stamp of the House of Mouse’s style. A semi-abstract underwater interlude speaks of Fantasia-like ambitions, displaying Dunbar’s fine-art leanings in style and concluding with a nod to Busby Berkeley’s choreographies. This bravura sequence is the most gorgeous of the tape, its swimming colours set prettily to the romantic whimsy of the music.

Frog Song got a theatrical run, playing before Paul’s catastrophic vanity feature Give My Regards to Broad Street (1984), while the song reached number three in the UK charts. The film went on to earn a Grammy nomination and win a BAFTA for best animated short (beating the Ringo Starr-narrated Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends). For all that success, the Rupert feature project collapsed as the rights situation grew more complicated.4 But a partnership with Dunbar was forged. The pair made more shorts together, and Dunbar illustrated Paul’s children’s book High in the Clouds (2005), which is now being adapted into a feature (apparently without Dunbar). This talented, self-effacing filmmaker gave the Paul McCartney Animation Universe its look.

Yet Dunbar hadn’t been Paul’s first choice for Frog Song. Paul had also considered Oscar Grillo, an exuberant Argentine who’d wound up, like Dunbar, at the heart of London’s advertising industry in the 1970s. He swiftly made a name for himself as a supreme animator and designer, with a bold graphic sensibility: in 1980, a reporter for Print magazine called his Dragon Productions studio “London’s hottest commercial shop.” Grillo knew Dunbar well, having worked with him at Dragon and animated on Lautrec.

Even for an ex-Beatle with Disney ambitions, Grillo proved too pricey. Paul was later reported as saying: “Oscar wanted to spend a lot of money on [Frog Song], which I don’t blame him for … [but] I thought it was a bit risky.” Yet he was in no doubt of Grillo’s talent, as the filmmaker had already directed the video of Linda’s “Seaside Woman”—the second short on my VHS.

Of the three films, this one made the least impression on the young me. Insofar as I remember it at all, it’s as a relatively uneventful interlude between two slices of vivid surrealism, lacking the famous character of the preceding film and the gloomy weirdness of the following one. Linda had written the song—the first she penned alone, according to Paul—during a stay in Jamaica, and the lyrics paint a cheery slice-of-life portrait of a local fisherman, his wife and his daughter: “Ride grey mule to market place each day / Sells her beads and baskets for seashell pay,” and so on. The film basically shows what the words tell, although some images add a new insinuation that tourism is threatening the peaceful island life.

This is a naïve, somewhat essentialising picture of a Caribbean society, complete with character designs that tend toward the crudely stereotypical. That aside, as I watch the film today, I see it is graphically the slickest of the three. It is a masterclass in interesting compositions, a riot of sharp angles and bold hues. In one sequence, the colours vanish as the girl and her cat run through a starkly graphic monochrome landscape. At another point, the frame takes the form of a series of bouncing shells. Everything is dynamic—the camera, the editing, the fluid animation—and as a result, the film makes something exciting of its thin narrative. So immersed are we in this fantasy Jamaica that, when Linda’s photos of the country appear among the end credits, they seem almost incongruous.

Like Frog Song after it, Seaside Woman was a hit, winning a Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1980. The Frog Song false start notwithstanding, Grillo remained in the McCartney orbit, directing a video for Linda’s song “Wide Prairie” which was released shortly after her death in 1998, as well as another short film inspired by her music, Shadow Cycle, which I’ve never seen: it played at a festival in 2000 but appears to have languished in the McCartney vaults ever since.

Strong as their creative partnership was, it wasn’t Grillo who sparked the Linda McCartney Animation Universe into being. This universe had begun two years before Seaside Woman with a (big) bang, as a comet struck a house in a very different film set to a very different song. It is this film, The Oriental Nightfish, that brings the notorious VHS to its conclusion.

The film opens on a stormy night in a bare apartment, where a thin robed woman—Linda herself?—vamps on a Wurlitzer organ. As the comet approaches, the lyrics kick in: “It was a Thursday night / I was working late / When I first caught sight / Of the Oriental Nightfish.” The cosmic force strikes the room, flooding it with rainbow stripes and a blast of flaming energy before transforming into giant wing-like forms, then back into a beam of liquid which envelops the now-naked woman and transports her through a series of abstract environments. Imagine the Star Gate passage in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but with more nudity and no hotel on the other side: the film ends with the woman dissolving into a vision of pure light.

It’s mostly the opening scene that frightened me. The expressionist lighting, the reverberating minor chords, the diabolical swirling keyboard, the mystery and intensity of that intrusive energy … it was overwhelming. The very idea of Thursdays was forever darkened in my mind. The fact that the lyrics barely develop from here—the abstract segments are set mostly to proggy instrumental noodling—only added to the inscrutability of it all. We, like the woman, are just passively hurtled through these strange spaces, with barely a hint as to the destination (much like someone on a gnarly trip, I guess). The image that represents the film on the VHS back cover is, I think it’s fair to say, sanitised.

The director is the late Ian Emes, who taught himself animation while at art school, where he was (aptly) impressed by the animated Beatles feature Yellow Submarine (1968). He forged a different path from Dunbar and Grillo (and indeed most independent UK animators of his generation) by steering clear of commercials, instead coming to be defined by his collaborations with rock musicians. He first caused a stir with French Windows (1972), his video for Pink Floyd’s “One of These Days.” Though made without the band’s permission, it pleased them so much that they hired him to create more visual material for their stage shows. It was at a Floyd gig that Linda and Paul discovered his work.

Like French Windows and other works of his, The Oriental Nightfish betrays Emes’s interest in architecture. Whereas Dunbar and Grillo lavish attention on the character animation in their respective films, the emphasis in Nightfish is on environments and geometric motifs. Like his contemporary Roger Mainwood, who directed a film set to Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn” (1979), he is interested in finding harmonies between musical structures and spatial configurations. But Emes’s account of the film’s genesis, told to BusinessLive in 2010, is more prosaic:

I got pissed on whisky and put the music on as loud as it would go, and lay on my back in the living room and let it wash over me. The whisky did indeed help, and I came up with this weird idea where alien forces enter this building where someone who looks like Linda McCartney is playing a Gothic Expressionistic Wurlitzer. This blonde female is penetrated and inhabited by the alien force, then she’s replicated, before becoming a comet that explodes.

The film was a bit weird and scary and a little bit sexual. Yet it was later put on Paul McCartney’s Rupert The Bear video for children. The kids who watched it years ago are now in their 20s, and they’ve set up an internet site called The Oriental Nightfish Haunted My Childhood. I guess it freaked them out and opened their imagination.

The site he mentions—actually a Facebook group—is a great resource, one the shaken child in me finds immensely validating. One poster writes: “I’m 42, and I received this video as a Xmas gift from a well-meaning but unknowing grandparent. I honestly don’t think I’ve ever truly recovered.” Another muses: “It makes you wonder what Linda put in her veggie burgers.”

I feel these comments deeply. For some, Bambi’s mum’s death is the primal trauma of animation watching. The Oriental Nightfish was mine. The film introduced me abruptly to the world of “adult animation” before I was fully aware such a thing existed. As much as Nightfish itself, its inclusion alongside the other films—and the continuity this implied between a familiar childhood world (Rupert’s) and the troubling dreamscapes of Emes’s imagination—made an impression on me.

In a way, the VHS is an aberration; when Rupert and the Frog Song was rereleased decades later on the DVD Paul McCartney: The Music and Animation Collection (alongside two other shorts he made with Dunbar), Linda’s films were notably absent. Yet there’s something enduringly interesting about the tape. Before the internet, it was rare for a rogue film like The Oriental Nightfish to come crashing accidentally into a child’s orbit, but now this happens easily on lightly regulated streaming platforms like YouTube. In this sense, and in this sense only, the VHS was prescient.

The VHS was released by Virgin Video.

Poignantly, Paul and co were recording “We All Stand Together” just around the time of the murder of John Lennon, who Paul says had encouraged him to make the Rupert film in the first place.

Decades later, “We All Stand Together” was reused in a supremely well-animated ad for The Great British Bake Off, made by Mikey Please and Dan Ojari of Robin Robin fame. Watch it here.

For more on the Rupert feature project, see Philip Norman’s Paul McCartney: The Biography.

I've never seen Oriental Nightfish - thanks for the link. What incredible animation and it says copyright 1977 which is even more incredible. Lots of the geometric passages look like they are CGI but clearly done by hand. Thanks for sharing and super interesting to read Ravi's insights on the production.

What I'd like to know is were you also creeped out by the animated corporate logo for McCartney's company "MPL Communications" that now precedes all his film / video work ?

I discovered recently that some people were mildly traumatised by it as children, and the discordant music track that accompanies it, composed by PM himself.

I animated the juggler featured in the short sequence at Len Lewis' studio Shootsey - my first real assignment at the studio after graduation and also oversaw the hand-rendering that I simply couldn't allow to be seen by the demanding client unless it was absolutely flawless, and it got me into hot water as a result since the rendering was divided up between several artists whose styles were all very slightly different.

I then spent many days and nights bringing it all together, much to Len's and McCartney's agents' annoyance since McCartney had to have a finished piece for the release of "Broad St" and time was running out - we spent a year making it in between other jobs and as the WIP went back and forth between the studio and the client.

*Len & Dunbar were old animation colleagues from the early days of their careers and Dunbar graciously directed McCartney to Len for the sequence when Len set up his own company.

R