The great feature animation studios often stand on a bedrock of short films. Many would never have made features at all had they not started with briefer works. Shorts are Petri dishes in which ideas, styles, technologies and directors fizz and develop, but they are often more: classics in their own right, worth revisiting as much as the longer films.

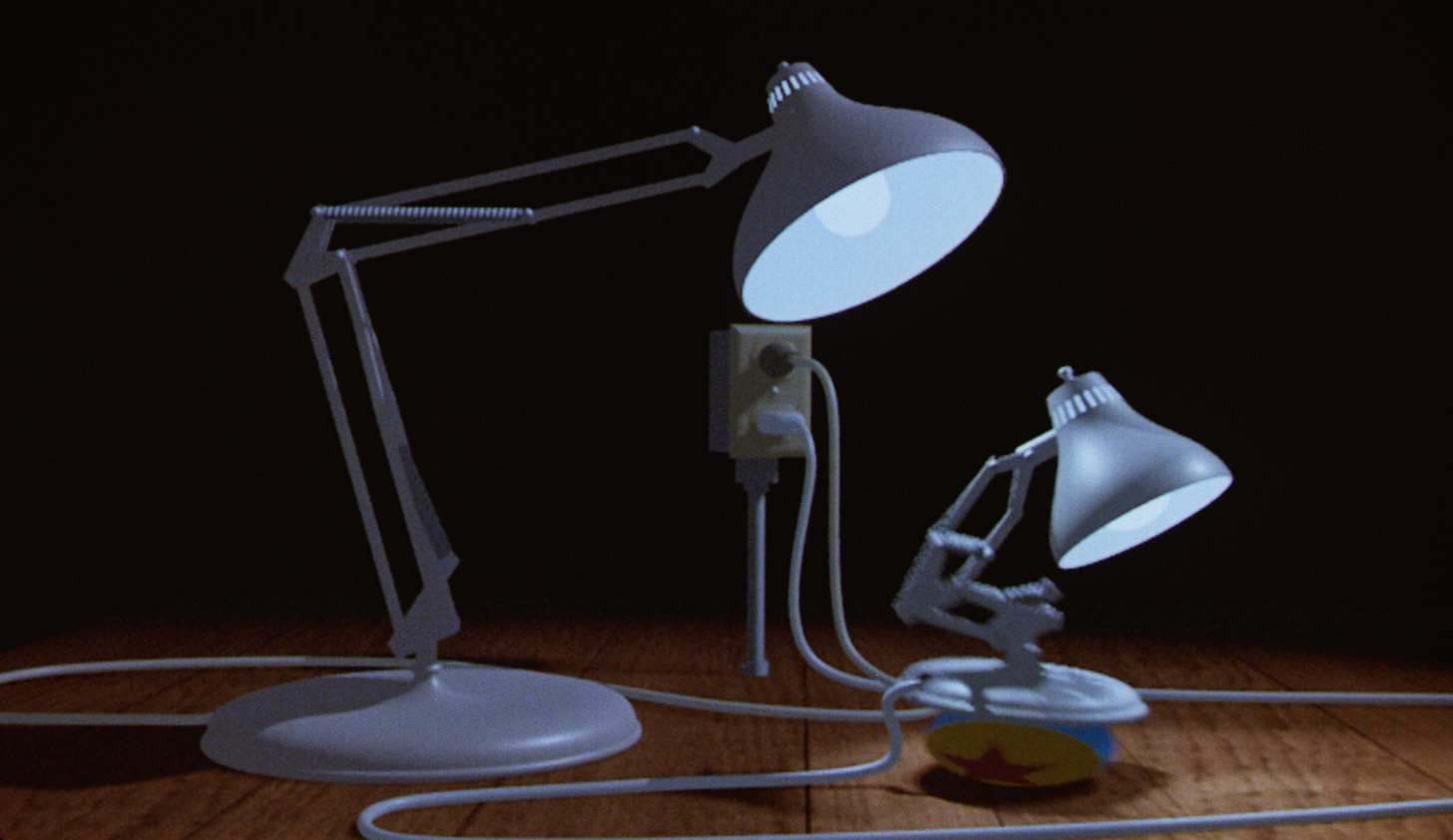

Disney started out when no one in the US was making animated features at all, and its early shorts road-tested one groundbreaking technology after another, be it synchronised sound in Steamboat Willie (1928) or the multiplane camera in The Old Mill (1937). Decades later, Pixar built itself up in a similar way, starting with shorts in which it could trial various aspects of its innovative CG pipeline: lighting in Luxo Jr. (1986), human animation in Geri’s Game (1997) and so on. Around the same time in the UK, Aardman was using shorts to explore the documentary-sound form that would eventually yield the Oscar-winning Creature Comforts (1989), while also launching its most famous characters, Wallace and Gromit, through another short, A Grand Day Out (1989). And for Studio Ghibli, shorts have offered a way to experiment with distribution: it has kept many of them more or less exclusive to its museum in Tokyo.1

Cartoon Saloon are no exception. Last month brought the distinctive Irish studio to the BFI Southbank in London, which dedicated a season to their work. Nestled among the screenings of their shimmering Oscar-nominated features—Song of the Sea (2014), The Breadwinner (2017), Wolfwalkers (2020) and so on—was a programme of their shorts, only a few of which I’d seen. It was to be followed by a Q&A with the studio’s founders, Tomm Moore, Nora Twomey and Paul Young.2 I bought a ticket.

Moore once said of the studio, “We wanted it to have a generic name, like Cartoon Saloon, so that we could have lots of people’s style and voice in it.” The programme lived up to that. Firstly, in a literal sense: lots of people are behind these shorts. Moore and Twomey have (co-)directed five of the studio’s six features but are only behind three of the eight shorts. The others are generally by first-time directors pulled from the ranks of the studio’s artists. Screecher’s Reach (2023), which was made for the Disney+ anthology series Star Wars: Visions Volume 2, is the directorial debut of Young himself, who is first and foremost Cartoon Saloon’s producer.

The shorts are also a disparate bunch in tone and style. Although the films are principally 2D, like the studio’s features, techniques like photo collage and stop motion slip in here and there. In look, they range from the Sylvain Chomet-like caricatures of Paul Ó Muiris’s The Ledge End of Phil (2014) to the spare painterly vistas of Julien Regnard’s Somewhere Down the Line (2014). The character designs in Screecher’s Reach and There’s a Monster in My Kitchen (2020), a two-minute spot directed for Greenpeace by Moore and Fabian Erlinghäuser, more closely resemble those in the features.

Watching the films, I was struck anew by how Cartoon Saloon are engaging storytellers. We know this from the features: you don’t get as big as they have by boring people. But telling a story in a short film—succinctly, elliptically, often with a tiny budget—is a different art. Every year at festivals, I see many visually arresting or conceptually interesting shorts which founder on a poorly assembled narrative; writing feels like the least-honed skill in this sector.

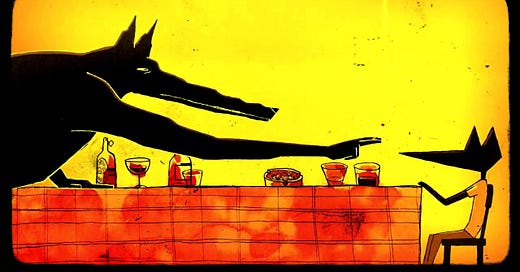

Yet from their first short, Twomey’s From Darkness (2002), Cartoon Saloon displayed the knack for it. Mystery courses through many of their shorts; ghosts and dangers trouble the characters. When the Inuit fisherman in From Darkness reels in a human skeleton, he reels us right in alongside it. In Old Fangs (2009), a trio of anthropomorphic animals who look like they’ve escaped from the pages of a Lewis Trondheim comic venture into a Grimm-like luxuriant forest full of latent threat, drawn toward a frightening house in its heart. This basic plot shape is echoed in Screecher’s Reach, where a group of young adventures venture deliberately into a banshee’s lair. And the titular beast in There’s a Monster in My Kitchen appears as a giant jaguar—although the real monsters are soon revealed to be the agents of deforestation in the Amazon.

In Somewhere Down the Line, the protagonist is haunted by something more nebulous. He is shown at different points in his life, from childhood to old age, always driving or being driven down identikit roads, from left to right of frame, often dissatisfied, sometimes angry. What we see of his life is cyclical: rupture, reconciliation, repeat. Yet roads imply progress. What is it he is driving toward—yearning for?

This film is based on another regular template in the Cartoon Saloon shorts: the cradle-to-grave story. An early example is Twomey’s Cúilín Dualach (2004), a quirky tale of a boy born with a backward-facing head who, it turns out, is narrating his life from beyond the grave. The format returns in Louise Bagnall’s Late Afternoon (2017), a hit of sorts for the studio: it earned an Oscar nomination and is still bringing in money—a rarity for a short—through sales to airlines and the sort.3 We meet Emily as an old woman with dementia; the story then follows the flux of her memories, alighting on important moments in her past.

It helps that the films are deftly storyboarded. (Hardly a surprise, given that several are directed by people who have storyboarded on Cartoon Saloon features and elsewhere, among them Bagnall, Regnard and Ó Muiris.) Films like From Darkness and Screecher’s Reach are dynamically staged: I like how the former opens and closes with close-ups of hands. Key twists in Somewhere Down the Line unfold unexpectedly, humorously, in the background of the image. Even as we are whisked almost randomly across times and places in Late Afternoon, swerving sometimes into abstraction, we are never disoriented, and the dynamism of these “memory sequences” contrasts powerfully with the relative stasis of the scenes in the present.

And although the shorts are stylistically disparate, elements familiar from the studio’s features abound. We see, early on, their talent for shape language: watch how, in the opening shot of Cúilín Dualach, what seems to be a range of bucolic green hills turns out to be the knees and breasts of a woman in labour. Their famous willingness to break with linear perspective is also in evidence in many shorts, although they also use it when appropriate: in Somewhere Down the Line, the monotony of the road is emphasised in shots of the car moving away from the camera into depth.

All this isn’t to say that the stories are always clear or complete. From Darkness ends with a striking metamorphosis, which seems to herald a second act that never comes. Then there is Old Fangs, the darkest and most atmospheric of the shorts (no surprise to learn that the director is Adrien Mérigeau—he of the extraordinary Genius Loci). The story begins as a spin on a fairy tale, complete with spooky woods and a big bad wolf. But in its final minutes, it becomes something else: a collage of troubling memories which limn the details of the story’s central relationship. In structure, this sequence is not unlike Late Afternoon, but things here are less explicit. I admire the commitment to ambiguity, and the colours, compositions and soundscape are wonderful throughout. Yet as with From Darkness, the ending feels more like an interruption than a conclusion.

Together, the eight shorts track the studio’s 25-year evolution in a way no one feature can. This may be why the three founders seemed moved when they took to the stage afterward: “I don’t think we’ve ever watched all those films all together in one place, and we just kept tearing up,” said Young. I was impressed to see that the house was full: 400-plus people had turned up on a weekend morning to watch a bunch of little-known animated shorts, which had rewarded them with their quality.

Now bring them out on Blu-ray.

Those who want to read more about how the short-film format has been used in animation could do worse than start with Christopher Holliday’s chapter “Features and Shorts” in The Animation Studies Reader.

THANK YOU FOR WRITING ABT THIS! Made my day!

Thanks for this. I enjoyed listening in.